Η Liang Dongmei (Jiangsu, 1973) είναι Κινέζα ζωγράφος, εγκατεστημένη στην Ελλάδα τα τελευταία δέκα χρόνια. Με σπουδές στο Τμήμα Καλών Τεχνών του Wuxi Vocational and Technical College of Arts and Crafts στην επαρχία Jiangsu και ενεργή παρουσία τόσο στην Κίνα όσο και διεθνώς, η Dongmei εντάσσει τη δουλειά της σε έναν διάλογο ανάμεσα στην ανατολική εικαστική παράδοση και στις σύγχρονες αναζητήσεις της δυτικής ζωγραφικής. Παράλληλα, συνδυάζει την δυτική εξπρεσιονιστική πινελιά με ένα ιδιαίτερα προσωπικό, συμβολικό λεξιλόγιο, εστιάζοντας στη σχέση φύσης και νου, την ένταση ανάμεσα σε τάξη και χάος, και την χαρά της ζωής. Η αναγνώρισή της από θεσμούς όπως η Πρεσβεία της Λαϊκής Δημοκρατίας της Κίνας στην Ελλάδα, το Μουσείο Τέχνης Jinling αλλά και από ιδιώτες συλλέκτες, με πιο εμβληματική τη συλλογή έργων της από τον Jackie Chan, υπογραμμίζει την απήχηση της δουλειάς της.

Στον πυρήνα του έργου της βρίσκεται μια εμμονική, σχεδόν τελετουργική προσήλωση στην ανθογραφία. Σειρές όπως Floral Shadows and Rainbow Garments, Flowering Season και The Mysterious Language of Flowers: The Chain of Life δείχνουν ότι το λουλούδι δεν αντιμετωπίζεται ως απλό διακοσμητικό στοιχείο, αλλά ως φορέας μιας κοσμοθεωρίας που αντλεί από το ανατολικό πνεύμα του ανιμισμού. Τα φυτικά της μοτίβα αναπαριστάνονται ως οργανισμοί σε διαρκή μετάβαση, συμβολίζοντας τη συνέχεια και τον κύκλο της ζωής και αναδεικνύοντας τη στενή, σχεδόν οργανική σχέση ανάμεσα στη ζωή και το φυσικό περιβάλλον.

Οι ανθογραφίες της Dongmei βρίσκονται σ’ έναν ιστορικό διάλογο με την ευρωπαϊκή παράδοση της νεκρής φύσης, ιδίως με τις ολλανδικές και φλαμανδικές ανθογραφίες του 17ου αιώνα. Στα έργα των Jan Brueghel the Elder, Ambrosius Bosschaert, Jan van Huysum, Rachel Ruysch κ.ά., το λουλούδι είναι προνομιακό μοτίβο μιας κοινωνίας πλούσιας και ταυτόχρονα βαθιά συνειδητοποιημένης για τη φθαρτότητα της ζωής. Οι εντυπωσιακές τους ανθοδέσμες, με την εκπληκτική περιγραφική ακρίβεια, προσφέρουν μια αισθητική απόλαυση και ταυτόχρονα μια ηθική υπενθύμιση ότι η ομορφιά είναι παροδική, ιδίως όταν απεικονίζονται μισομαραμένα πέταλα, έντομα ή όταν συνοδεύονται από μισοσβησμένα κερά, νεκροκεφαλές ή άλλα σημάδια φθοράς που μετατρέπουν μια όμορφη ανθογραφία σε σιωπηλή vanitas, όπου το λουλούδι γίνεται σύμβολο του χρόνου που περνά και της ματαιότητας (Κολοκοτρώνης, 1992: 24-33).

Στο κλασικό βιβλίο The Art of Describing, η Svetlana Alpers υποστηρίζει ότι η ζωγραφική των Κάτω Χωρών του 17ου αιώνα εκφράζει μια «οπτική» κουλτούρα, που δίνει έμφαση στην περιγραφή αυτού που βλέπει το μάτι, σε αντίθεση με την «κειμενική» παράδοση της ιταλικής Αναγέννησης και την αφηγηματική ζωγραφική που στηρίζεται σε ιστορίες (Alpers 1983). Αντί για σκηνές με σαφή πλοκή, η ολλανδική ζωγραφική, ιδιαίτερα οι ανθογραφίες, προτιμά τη λεπτομερή καταγραφή της επιφάνειας και του ορατού κόσμου. Μέσα από αυτό το πρίσμα, η ανθογραφία μπορεί να θεωρηθεί κατεξοχήν «περιγραφικό» είδος καθώς γεννιέται από μια οπτική και όχι από μια αφηγηματική κατανόηση του κόσμου.

Σ’ αυτό το θεωρητικό πλαίσιο, η Liang Dongmei μπορεί να ιδωθεί ως καλλιτέχνιδα που συνομιλεί με την ολλανδική περιγραφική παράδοση των ανθογραφιών, αλλά ταυτόχρονα την επεκτείνει με το βλέμμα της Ανατολής. Αν οι ιστορικές ανθογραφίες είναι εντυπωσιακές, πλήρως περιγραφικές καταγραφές μιας ιδανικής ανθοδέσμης, η Dongmei φέρνει το βλέμμα πιο κοντά, σε «κοντινά πλάνα» ρευστών φυτικών μορφών, όπου η επιφάνεια δεν είναι σταθερή αλλά βρίσκεται σε συνεχή κίνηση. Τα άνθη της δεν είναι τακτοποιημένα σε βάζα, ούτε περιορισμένα σε μια αυστηρή κεντρική σύνθεση· απλώνονται στην επιφάνεια του μουσαμά σαν σπείρες φωτός και νερού, δημιουργώντας την αίσθηση ενός πεδίου ενέργειας και όχι μιας στατικής, τεχνητά φωτισμένης ανθοδέσμης.

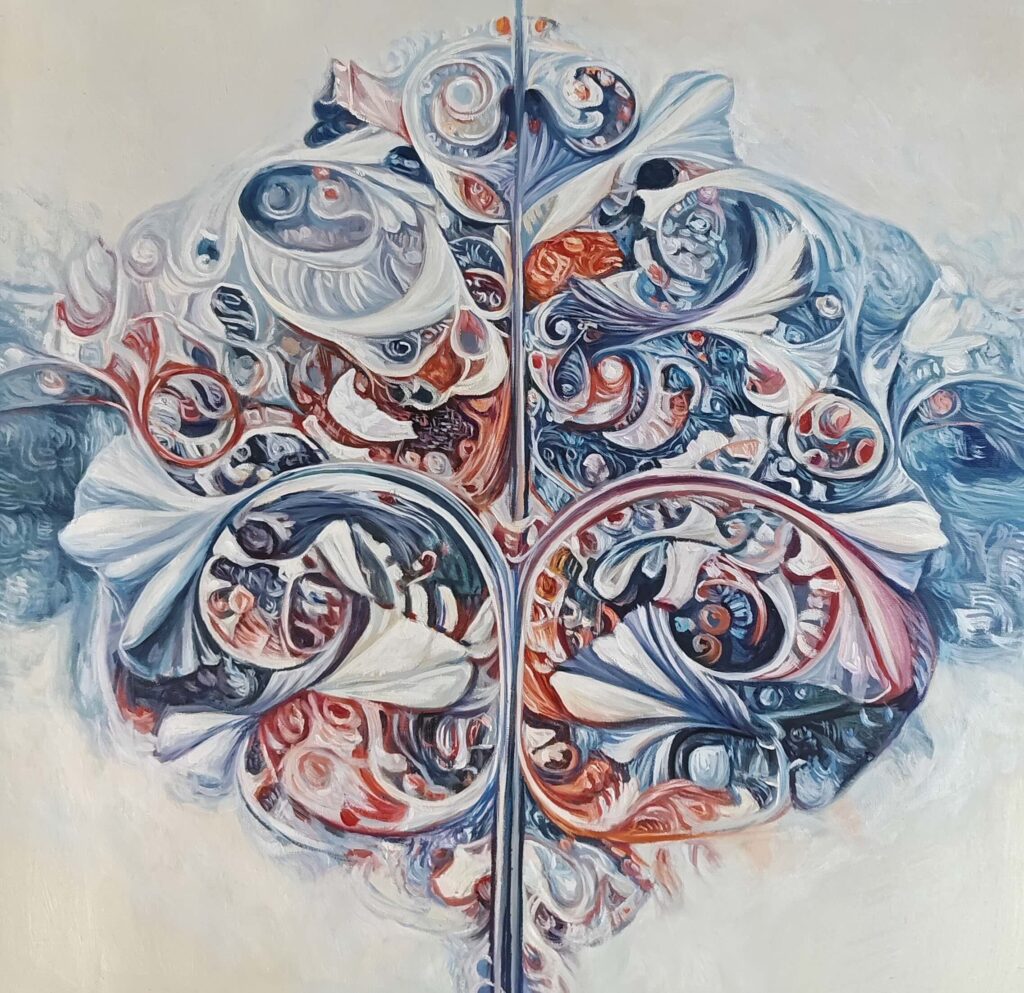

Η τεχνική αυτή δεν είναι αποτέλεσμα μόνο διαισθητικής χειρονομίας. Η Dongmei έχει αναπτύξει μια πολυεπίπεδη αφηρημένη μέθοδο, την οποία εφαρμόζει και σε άλλες σειρές έργων της, όπως στη σειρά Kaleidoscope. Πρόκειται για μια «δομημένη αφαίρεση» (Structured Abstraction), όπου ο πίνακας χτίζεται μέσα από διαδοχικά στρώματα χρώματος και χειρονομίας. Κάθε στρώση κρατά ίχνη συναισθηματικής έκρηξης, αλλά ταυτόχρονα υπάγεται σε μια αυστηρότερη λογική οργάνωσης, ρυθμού και συμμετρίας. Η διαδικασία «στρώση / επικάλυψη / διόρθωση / αναδιαμόρφωση», μετατρέπει τη ζωγραφική επιφάνεια σε πεδίο όπου το τυχαίο και το υπολογισμένο, το συναισθηματικό και το λογικό, συνυπάρχουν σε μια δυναμική ισορροπία.

Στις ανθογραφίες της, αυτή η μέθοδος εμφανίζεται σαν εκρήξεις λαμπερών χρωματικών πεδίων και επαναλαμβανόμενων ρυθμών, ώστε τα πέταλα και τα φύλλα να μοιάζουν με «μονάδες» ενός εσωτερικού μαθηματικού μοτίβου. Η παλέτα της, εστιασμένη στα έντονα γαλάζια, ροζ, πορτοκαλί, κίτρινα και πράσινα, ενισχύει την εντύπωση της παλλόμενης ενέργειας. Αν οι ανθογραφίες του 17ου αιώνα στοχάζονται πάνω στην παροδικότητα της ύλης, η Dongmei προτείνει μια μετατόπιση του βλέμματος, από την έμφαση στην υλική φθορά προς την έμφαση στην αδιάκοπη ενεργειακή ροή, από το τέλος προς τον κύκλο.

Κάθε σύνθεσή της χαρακτηρίζεται από σπειροειδείς κινήσεις και ρευστές καμπύλες, ώστε τα πέταλα να μοιάζουν με κύματα φωτός ή νερού. Τα λουλούδια της δεν προβάλλονται πάνω σε ένα ουδέτερο ή σκοτεινό περιβάλλον, όπως στους Ολλανδούς και Φλαμανδούς ζωγράφους που αναδεικνύουν με αυτό τον τρόπο τη θεατρικότητα της σύνθεσης και της ύλης. Αντίθετα, ως μια διαρκής ροή χρωμάτων, μοιάζουν να αναδύονται από ένα ήδη ενεργοποιημένο πεδίο, το οποίο διαλύει τα όρια ανάμεσα στη φύση και το σύμπαν, εκεί όπου η διάκριση μεταξύ μικροκλίμακας (άνθος) και μακροκλίμακας (σύμπαν) μοιάζει να αίρεται.

Σε αυτό το πλαίσιο, η ζωγραφική της Liang Dongmei μπορεί να διαβαστεί ως μια σύγχρονη, διαπολιτισμική αναθεώρηση της ανθογραφίας: μια μετατόπιση από την επίδειξη αφθονίας και τη στοχαστική vanitas του 17ου αιώνα προς μια λυρική, ανιμιστική αντίληψη της φύσης. Ενώ οι Ολλανδοί και Φλαμανδοί ζωγράφοι χρησιμοποιούν το λουλούδι για να μιλήσουν για το τέλος, η Dongmei το χρησιμοποιεί για να μιλήσει για τη συνέχεια. Μέσα από τα έργα της, το λουλούδι παύει να είναι απλώς σύμβολο της φθοράς και γίνεται εικαστικός φορέας ενός μυστικού, αδιάκοπου κύκλου ζωής, όπου η δομημένη αφαίρεση, η χρωματική έκρηξη και η ανιμιστική ματιά συνυπάρχουν σε μια ενιαία, αναγνωρίσιμη εικαστική γλώσσα.

Γιάννης Κολοκοτρώνης

Καθηγητής Ιστορίας και Θεωρίας της Τέχνης -Τμήμα Αρχιτεκτόνων Μηχανικών / Δ.Π.Θ.

Yannis Kolokotronis, The Flowers of Liang Dongmei

Liang Dongmei (Jiangsu, 1973) is a Chinese painter who has been based in Greece for the past ten years. Having studied at the Fine Arts Department of the Wuxi Vocational and Technical College of Arts and Crafts in Jiangsu province and maintaining an active presence both in China and internationally, Dongmei situates her work in a dialogue between Eastern artistic traditions and the contemporary concerns of Western painting. At the same time, she combines a Western expressionist brushstroke with a highly personal symbolic vocabulary, focusing on the relationship between nature and mind, the tension between order and chaos, and the joy of life. Her recognition by institutions such as the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Greece and the Jinling Art Museum, as well as by private collectors – most notably the acquisition of her works by Jackie Chan – underscores the reach and intercultural resonance of her practice.

At the core of her work lies an obsessive, almost ritualistic commitment to flower painting. Series such as Floral Shadows and Rainbow Garments, Flowering Season and The Mysterious Language of Flowers: The Chain of Life show that the flower is not treated as a mere decorative element, but as a bearer of a worldview informed by the Eastern spirit of animism. Her floral motifs are rendered as organisms in constant transition, symbolizing continuity and the cycle of life, and highlighting the close, almost organic bond between life and the natural environment.

Dongmei’s flower paintings are inscribed in a historical dialogue with the European tradition of still life, particularly with Dutch and Flemish flower pieces of the seventeenth century. In the works of Jan Brueghel the Elder, Ambrosius Bosschaert, Jan van Huysum, Rachel Ruysch and others, the flower becomes a privileged motif within a society that is both affluent and acutely aware of the transience of life. Their impressive bouquets, depicted with astonishing descriptive precision, offer aesthetic pleasure and at the same time a moral reminder that beauty is ephemeral – especially when half-withered petals, insects, or the presence of half-burnt candles, skulls and other signs of decay transform a beautiful flower painting into a silent vanitas, in which the flower becomes a symbol of the passage of time and of human vanity (Kolokotronis 1992: 24–33).

In her classic book The Art of Describing, Svetlana Alpers argues that seventeenth-century Dutch painting expresses a “visual” culture that privileges the description of what the eye sees, in contrast to the “textual” culture of the Italian Renaissance and its narrative paintings based on stories (Alpers 1983). Rather than scenes with a clear plot, Dutch painting – and especially flower painting – favours the meticulous recording of surfaces and of the visible world. From this perspective, flower painting can be understood as a paradigmatically “descriptive” genre, grounded in a visual rather than a narrative understanding of the world.

Within this theoretical framework, Liang Dongmei can be seen as an artist who engages with the Dutch descriptive tradition of flower painting, while at the same time extending it through an Eastern gaze. If historical flower pieces are impressive, fully descriptive records of an ideal bouquet, Dongmei brings the viewpoint closer, to “close-up” images of fluid botanical forms, where the surface is no longer stable but in constant motion. Her flowers are not arranged in vases, nor confined within a strict central composition; they unfold across the surface of the canvas like spirals of light and water, creating the impression of an energetic field rather than a static, artificially lit bouquet.

This technique is not the result of intuitive gesture alone. Dongmei has developed a multi-layered abstract method, which she also applies in other series, such as Kaleidoscope. It is a form of “structured abstraction”, in which the painting is built up through successive layers of colour and gesture. Each layer retains traces of emotional outburst, while simultaneously submitting to a stricter logic of organization, rhythm and symmetry. The process of “layering / overpainting / correction / reconfiguration” transforms the painted surface into a field where the accidental and the calculated, the emotional and the rational, coexist in a dynamic equilibrium.

In her flower paintings, this method appears as eruptions of luminous colour fields and recurring rhythms, so that petals and leaves resemble “units” within an internal mathematical pattern. Her palette – concentrated on intense blues, pinks, oranges, yellows and greens – reinforces the impression of pulsating energy. If seventeenth-century flower painting reflects on the transience of matter, Dongmei proposes a shift in emphasis: from material decay to continuous energetic flow, from the end to the cycle.

Each of her compositions is characterized by spiral movements and fluid curves, so that the petals appear like waves of light or water. Her flowers do not emerge against a neutral or dark background, as in the case of Dutch and Flemish painters who use such grounds to heighten the theatricality of composition and matter. Instead, as a continuous flow of colour, they seem to arise from an already activated field that dissolves the boundaries between nature and cosmos, where the distinction between micro-scale (the flower) and macro-scale (the universe) appears to be suspended.

In this light, Liang Dongmei’s painting can be read as a contemporary, intercultural rethinking of flower painting: a shift away from the display of abundance and the contemplative vanitas of the seventeenth century towards a lyrical, animistic conception of nature. Whereas Dutch and Flemish painters use the flower to speak of endings, Dongmei uses it to speak of continuity. Through her work, the flower ceases to be merely a symbol of decay and becomes a pictorial vehicle of a secret, ceaseless cycle of life, in which structured abstraction, chromatic explosion and an animistic gaze coalesce into a single, recognizable visual language.

Yannis Kolokotronis

Professor of Art History and Theory -Department of Architecture, Democritus University of Thrace

Bibliography