Η σύνθεση ξεφεύγει από τα συμβατικά όρια του καμβά: μια σταυροειδής διάταξη από τέσσερα τελάρα 150 x 150 εκ., προσαρμοσμένα περιμετρικά γύρω από ένα κεντρικό τετράγωνο τελάρο, σχηματίζουν ένα ενιαίο σύνολο. Αυτή η διαμόρφωση δεν είναι μόνο μια μηχανική επέκταση της ζωγραφικής επιφάνειας, αλλά μια σκόπιμη αρχιτεκτονική σύλληψη του θείου ως πολιτισμικού συμβόλου, όπως έχει εγγραφεί στη δυτική εικονογραφική παράδοση. Η σταυροειδής δομή ενεργοποιεί έναν καθολικό κώδικα: ακόμη και αν η μορφή δεν αναπαριστούσε ρητά τον Χριστό, η τοποθέτησή της στο κέντρο του σταυρού θα συσχετιζόταν υποσυνείδητα με τη δραματική σχέση ανάμεσα στο σώμα και στο πεπρωμένο, θυμίζοντας την εικονογραφική παράδοση της Σταύρωσης.

Στο έργο του Λεονταρίδη, το σταυρικό σχήμα δεν αναπαράγει απλά μια θρησκευτική εικόνα, αλλά μετατρέπεται σε συμβολικό εργαλείο που προσδίδει στην ανθρώπινη μορφή υπαρξιακή πυκνότητα και υπογραμμίζει την ένταση ανάμεσα στη θνητότητα και την υπέρβαση. Στο κέντρο δεσπόζει το φωτεινό πρόσωπο του Χριστού σε ένα ουράνιο τοπίο από σύννεφα και γαλήνιο φως. Η πραότητα, η συμπόνια και η πνευματική γαλήνη συνθέτουν μια εικόνα λυτρωτικής θείας παρουσίας.

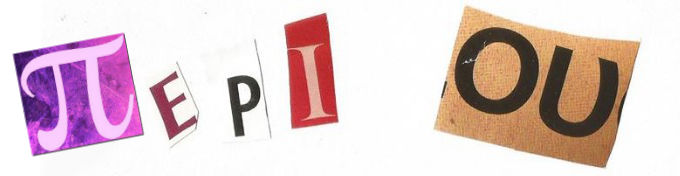

Στις τέσσερις προεξοχές της trample-l’oeil ξύλινης κατασκευής, εμφανίζονται τα γράμματα ΙΝΒΙ, λειτουργώντας ως σύμβολα που συνδέουν τη ζωγραφισμένη επιφάνεια με το ψευδαισθητικό αρχιτεκτονικό της πλαίσιο, δίνοντας στο έργο την εντύπωση ενός ξύλινου εικονοστασίου. Τα περιφερειακά τελάρα, χαρακτηριστικά στην πρακτική των πολυσχηματικών καμβάδων της τέχνης του Θανάση Λεονταρίδη ενισχύουν τη συμβολική διάσταση της σύνθεσης. Ο Λεονταρίδης αξιοποιεί ένα φορτισμένο σχήμα όχι για να επαναλάβει το νόημα της χριστιανικής Σταύρωσης, αλλά για να δείξει πώς ένας καθολικός κώδικας μπορεί να ενεργοποιηθεί σε σύγχρονο εικαστικό πλαίσιο, όπου η ανθρώπινη μορφή γίνεται τόπος υπαρξιακού αναστοχασμού. Είτε προσεγγιστεί ως θρησκευτική εικόνα είτε όχι, το έργο αναδεικνύει τη διαλεκτική μεταξύ του ατόμου και του εσωτερικού εαυτού, ένα οπτικό αποτύπωμα της έντασης μεταξύ θλίψης και αντοχής. (https://www.periou.gr/giannis-kolokotronis-i-efevretikotita-tou-thanasi-leontaridi/)

Γύρω στο 1900, ο Κωνσταντίνος Παρθένης ζωγράφισε τον εμβληματικό Χριστό (λάδι σε μουσαμά, 200 x 200 εκ. Εθνική Πινακοθήκη, Αθήνα https://www.nationalgallery.gr/artwork/o-christos/), μια μνημειώδη κυκλική σύνθεση όπου το πρόσωπο του Χριστού παρουσιάζεται σε υπερφυσική κλίμακα. Με υπνωτιστική έκφραση και το βλέμμα εκστατικά στραμμένο προς τα πάνω, ο Χριστός του Παρθένη, λούζεται στο μπλε χρώμα, δημιουργώντας μια ατμόσφαιρα μυστικισμού και βαθιάς ενδοσκόπησης. Ο Παρθένης μέσα από τα εργαλεία και τις τεχνικές της Art Nouveau και του γαλλικού συμβολισμού, εκσυγχρόνισε το ιερό εξιδανικεύοντας και σχεδόν εξαϋλώνοντας τη μορφή, ώστε να απεικονίσει μια θεότητα που έχει υπερβεί την ανθρώπινη εμπειρία.

Και στα δύο έργα, χωρίς περιττά αφηγηματικά στοιχεία, το βλέμμα του θεατή κατευθύνεται αποκλειστικά προς τη μορφή του Χριστού: στου Λεονταρίδη, σε μια λουσμένη στο φως μορφή με το βλέμμα στραμμένο προς τη γη. Στου Παρθένη, σε ένα οραματικό μπλε πορτρέτο στραμμένο προς το υπερκόσμιο. Έτσι, προκύπτουν δύο διαμετρικά αντίθετες αλλά εξίσου αυθεντικές εκδοχές του θείου. Με την απόσταση ενός αιώνα, ο Παρθένης μετασχηματίζει τον δραματικό πόνο και την υπαρξιακή ένταση του Πάθους σε μυστικιστική αναζήτηση του νοήματος της θυσίας και της θεϊκής παρουσίας. Αντίθετα, στον Λεονταρίδη η σταυρική σύνθεση γίνεται εικονογραφικός καμβάς ανθρωποκεντρικής θεώρησης της θεότητας. Οι δύο εκδοχές, αποτυπώνουν τη μετάβαση από τον μυστικισμό της εσωτερικής αγωνίας του Πάθους προς μια πιο φωτεινή και ανθρωποκεντρική θεώρηση, όπου ο Χριστός δεν βιώνεται μόνο ως πάσχων, αλλά και ως φορέας ελπίδας.

Ανάμεσα στις δύο αυτές εκδοχές και σε εντελώς διαφορετική κατεύθυνση, ο Salvador Dalí στο Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) (1954 Λάδι σε καμβά; 194.3 x 123.8 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Nέα Υόρκη) προσεγγίζει το θείο μέσω της μεταφυσικής και της επιστημονικής φαντασίας. Ο Εσταυρωμένος αιωρείται σ’ έναν «απλωμένο» υπερκύβο, ένα τετραδιάστατο γεωμετρικό σχήμα που υποδηλώνει την ύπαρξη ανώτερων διαστάσεων πέρα από τον ορατό κόσμο. Όπως εξήγησε ο Dali: «Η προέκταση ενός κύβου στην τέταρτη διάσταση δημιουργεί έναν υπερκύβο. Ένας κύβος διαθέτει έξι έδρες, ενώ ένας υπερκύβος έχει οκτώ «κυψέλες» (όπου «κυψέλη» είναι ένα τρισδιάστατο όριο ενός 4D αντικειμένου). Στον συγκεκριμένο πίνακα απεικονίζεται ένας «ξεδιπλωμένος» υπερκύβος: όπως ακριβώς μπορεί κάποιος να ξεδιπλώσει τις έξι έδρες ενός 3D κύβου στο δισδιάστατο επίπεδο ώστε να προκύψει το σχήμα ενός σταυρού, έτσι μπορεί να ξεδιπλωθεί και ένας υπερκύβος σε έμια τρισδιάστατη σταυροειδή δομή.» https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/salvador-dali)

Ο Dalí αποφεύγει την απεικόνιση του πόνου ή της ανθρώπινης θνητότητας, ανακαλύπτοντας εκ νέου το ιερό μέσω της γεωμετρίας της τέταρτης διάστασης και την τάξη του σύμπαντος. Σε αντιδιαστολή με τον μυστικιστικό εξπρεσιονισμό του Παρθένη και τον ανθρωποκεντρικό συμβολισμό του Λεονταρίδη, ο Dalí προτείνει έναν Χριστό-γέφυρα ανάμεσα στην θεϊκή γεωμετρία και στη σύγχρονη επιστημονική φαντασία· μια θεότητα που αποκαλύπτεται ως υπερδιάστατη ενέργεια. Με κοινό παρονομαστή τη γεωμετρία, είτε ως 4D μαθηματική δομή στον Dalí είτε ως σταυρική πολιτισμική αρχιτεκτονική στον Λεονταρίδη, το θείο αναδιαμορφώνεται μέσα από δύο διαφορετικές χωρικές συλλήψεις της ζωγραφικής.

Γιάννης Κολοκοτρώνης

Καθηγητής Ιστορίας και Θεωρίας της Τέχνης

Τμήμα Αρχιτεκτόνων Μηχανικών Δ.Π.Θ.

Yannis Kolokotronis, An Existential Imprint: The Christ of Thanasis Leontaridis

The composition of the work transcends the conventional boundaries of the canvas: a cruciform arrangement of four 150 × 150 cm stretchers, mounted around a central square panel, forms a unified whole. This configuration is not merely a mechanical extension of the pictorial surface but a deliberate architectural conception of the divine as a cultural symbol embedded within the Western iconographic tradition. The cross-shaped structure activates a universal code: even if the figure did not explicitly represent Christ, its placement at the centre of the cross would subconsciously evoke the dramatic interplay between body and destiny, recalling the long-standing iconography of the Crucifixion.

In Leontaridis’s work, the cross does not function as a straightforward reiteration of a religious image; instead, it becomes a symbolic device that lends existential density to the human figure and underscores the tension between mortality and transcendence. At the centre shines the luminous face of Christ, set against a celestial landscape of clouds and tranquil light. Gentleness, compassion, and spiritual serenity coalesce into a vision of redemptive divine presence.

At the four projecting corners of the trompe-l’œil wooden construction appear the letters INBI, serving as symbols that bind the painted surface to its illusory architectural frame, giving the work the appearance of a wooden icon-box. The peripheral stretchers, characteristic of Leontaridis’s distinctive use of multi-shaped canvases, reinforce the symbolic resonance of the overall composition. Through this cruciform architecture, Leontaridis employs a charged visual form not to reiterate the meaning of the Christian Crucifixion but to demonstrate how a universal code can be activated within a contemporary artistic context, where the human figure becomes a site of existential reflection. Whether approached as a religious image or not, the work foregrounds the dialectic between the individual and the inner self—an optical imprint of the tension between sorrow and endurance. (https://www.periou.gr/giannis-kolokotronis-i-efevretikotita-tou-thanasi-leontaridi/)

Around 1900, Konstantinos Parthenis painted his emblematic Christ (oil on canvas, 200 × 200 cm, National Gallery, Athens https://www.nationalgallery.gr/artwork/o-christos/), a monumental circular composition in which the face of Christ appears on a supernatural scale. With a hypnotic expression and the gaze lifted ecstatically upward, Parthenis’s Christ is bathed in blue light, creating an atmosphere of mysticism and profound introspection. Drawing on Art Nouveau and French Symbolism, Parthenis modernised the sacred, idealising and almost dematerialising the figure in order to depict a deity surpassing the limits of human experience.

In both works, devoid of extraneous narrative elements, the viewer’s attention is directed solely toward the figure of Christ: in Leontaridis, a radiantly lit form oriented toward the earth; in Parthenis, a visionary blue portrait oriented toward the transcendent. The result is two diametrically opposed yet equally authentic manifestations of the divine.

With a distance of nearly a century, Parthenis transforms the dramatic pain and existential tension of the Passion into a mystical search for the meaning of sacrifice and divine presence. Leontaridis, conversely, uses the cruciform structure as an iconographic field of spiritual elevation and redemption. Together, these two interpretations reveal a broader conceptual shift—from the mysticism of inner anguish toward a more luminous, human-centred understanding of divinity, in which Christ is experienced not only as the suffering figure but also as a bearer of hope.

Between these two approaches, and moving in an entirely different direction, Salvador Dalí in Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) (1954, oil on canvas; 194.3 × 123.8 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/salvador-dali) approaches the divine through the lens of metaphysics and scientific imagination. The Crucified Christ hovers before an “unfolded” hypercube— a four-dimensional geometric structure that suggests the existence of higher dimensions beyond the visible world. As Dalí explained: “Extending a cube into the fourth dimension creates a hypercube. A cube possesses six faces, whereas a hypercube contains eight ‘cells’ (a ‘cell’ being a three-dimensional boundary of a four-dimensional object). This painting depicts an unfolded hypercube: just as one can unfold the six faces of a three-dimensional cube into the two-dimensional shape of a cross, a hypercube can likewise be unfolded into a three-dimensional cruciform structure.”

Dalí avoids any depiction of pain or human mortality, reinventing the sacred through the geometry of the fourth dimension and the order of the cosmos. In contrast to Parthenis’s mystical expressionism and Leontaridis’s human-centred symbolism, Dalí proposes a Christ who functions as a bridge between divine geometry and contemporary scientific imagination— a deity who is revealed as hyperdimensional energy. With geometry as their shared denominator— whether as a four-dimensional mathematical construct in Dalí or as a cruciform cultural architecture in Leontaridis— the divine is reconfigured through two markedly different spatial conceptions of painting.

Yannis Kolokotronis

Professor of Art History and Theory

Department of Architecture, Democritus University of Thrace