Μια εικόνα γεννιέται από τις λέξεις; Ναι, όταν δεν περιγράφουν απλώς τον κόσμο, αλλά ενεργοποιούν τη μνήμη και τη φαντασία του θεατή. Μπορούν οι λέξεις να αντικαταστήσουν ένα τοπίο; Ναι, αν το ζητούμενο είναι το βίωμα και όχι η περιγραφή: στο βίωμα ξυπνούν η μνήμη, η επιθυμία, η νοσταλγία, η προσδοκία. Γιατί ένας ζωγράφος, μέσα από έναν ποιητικό στοχασμό ζωγραφίζει ένα τοπίο; Επειδή το τοπίο είναι τρόπος σκέψης, όχι μόνο φύση. Επειδή οι ερωτήσεις «πού τελειώνει το βλέμμα;» «τί σημαίνει ορίζοντας» και «τί ψάχνει να βρει ένα καράβι;» είναι διαχρονικές ερωτήσεις, που μας οδηγούν να αναζητήσουμε νόημα, όχι απλώς προορισμούς.

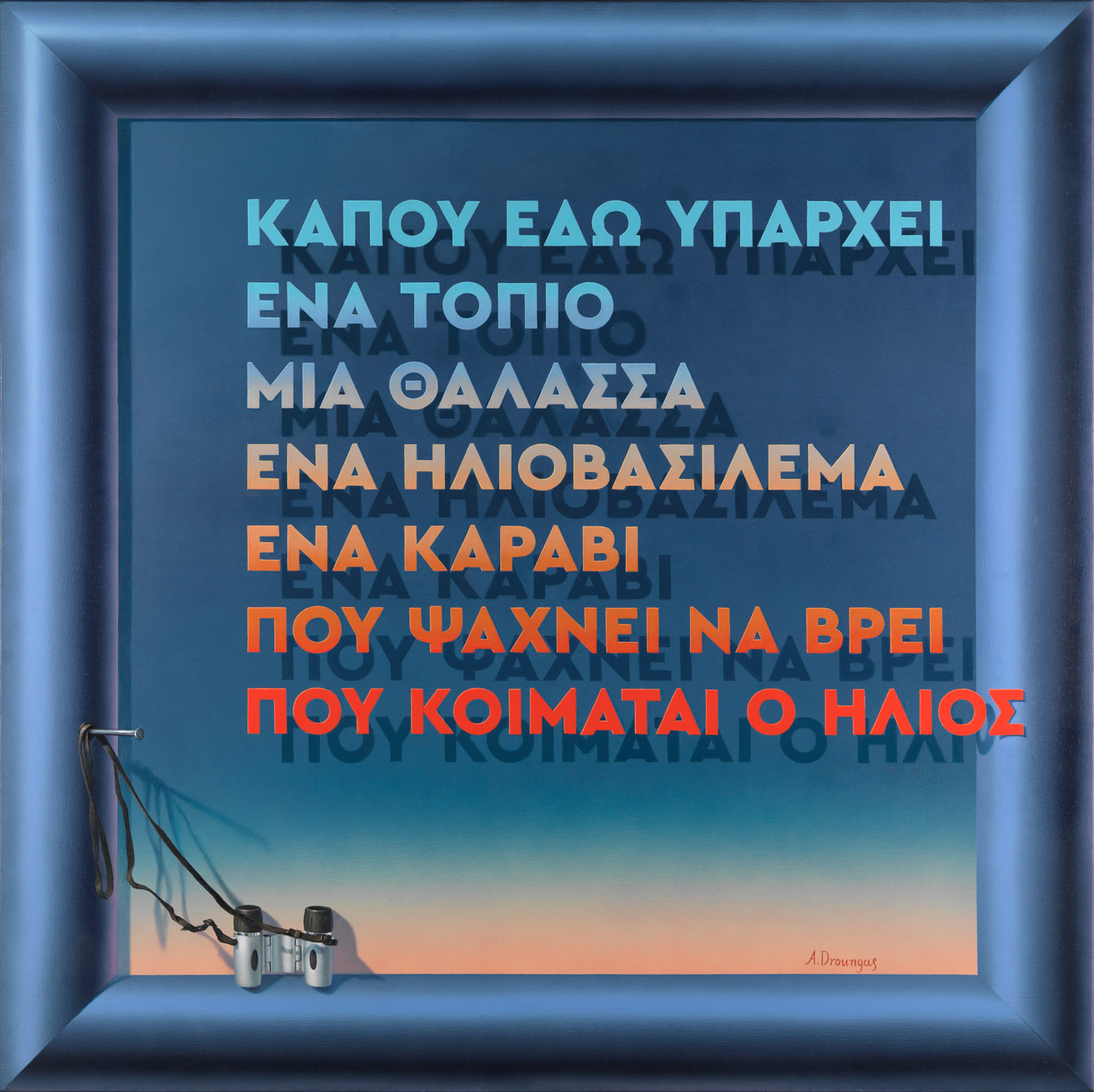

ΚΑΠΟΥ ΕΔΩ ΥΠΑΡΧΕΙ

ΕΝΑ ΤΟΠΙΟ

ΜΙΑ ΘΑΛΑΣΣΑ

ΕΝΑ ΗΛΙΟΒΑΣΙΛΕΜΑ

ΕΝΑ ΚΑΡΑΒΙ

ΠΟΥ ΨΑΧΝΕΙ ΝΑ ΒΡΕΙ

ΠΟΥ ΚΟΙΜΑΤΑΙ Ο ΗΛΙΟΣ

Το Εννοιολογικό Τοπίο (2023) του Αχιλλέα Δρούγκα δεν είναι ένας τόπος που αντιγράφεται, αλλά ένα μέρος για στοχασμό. Παύει να είναι μια φυσιολατρική αναπαράσταση και το Εννοιολογικό Τοπίο μετατρέπεται σε ένα σημειωτικό πεδίο, μια σκηνή όπου τα πράγματα δεν είναι μόνον αυτό που φαίνονται, αλλά και αυτό που σημαίνουν. Για τους φανατικούς θαυμαστές της ζωγραφικής του, ένα τέτοιο έργο σημειωτικής της εικόνας, δεν προκαλεί έκπληξη. Ο Δρούγκας μας έχει συνηθίσει σε μια τέχνη αντισυμβατική, εννοιολογική, συμβολική και αλληγορική, μια τέχνη εντυπωσιακά πρωτότυπη, που, εξαντλώντας τις δυνατότητες του ακραίου ρεαλισμού, δεν εγκλωβίζεται στη φωτογραφική πιστότητα, αλλά την υπερβαίνει εμπλέκοντας τον θεατή σε μια διαδικασία ερμηνείας.

Ο Αχιλλέας Δρούγκας συγκαταλέγεται στις ιστορικές φυσιογνωμίες της σύγχρονης ελληνικής τέχνης, με διεθνή διαδρομή που ξεκινά από τις αρχές της δεκαετίας του 1970.[i] Η αναγνώριση αυτή δεν αφορά μόνο την κριτική υποδοχή του έργου του, αλλά και τη θεσμική του καταγραφή, αφού έργα του εντάσσονται σε σημαντικές δημόσιες και πανεπιστημιακές συλλογές, επιβεβαιώνοντας τη θέση του σε ένα ευρύτερο, διεθνές πλαίσιο (Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)[ii], Tate Gallery (Λονδίνο)[iii], Portland Museum of Art[iv], Buffalo AKG Art Museum[v], The University of Virginia[vi], Cornell University[vii], Victoria and Albert Museum, National Museum of Wales, Bibliothèque nationale de France (Παρίσι)[viii], British Government Art Collection[ix] Εθνική Πινακοθήκη[x] μεταξύ άλλων).

Σ’ αυτήν τη λογική του ακραίου ρεαλισμού, το τοπίο μπορεί να γεννηθεί από τις λέξεις, όχι επειδή οι λέξεις αντικαθιστούν την εικόνα, αλλά επειδή ενεργοποιούν την εμπειρία και την προσδοκία, πριν αυτή γίνει εικόνα. Το «κάπου εδώ υπάρχει ένα τοπίο» είναι μια πρόσκληση στο βλέμμα του θεατή. Και «το καράβι που ψάχνει να βρει πού κοιμάται ο ήλιος» είναι μια αλληγορία της ανθρώπινης κατάστασης, μια αναζήτηση στον ορίζοντα για το νόημα της ζωής. Έτσι, το εννοιολογικό τοπίο δεν είναι μια απεικόνιση της θάλασσας ή του ηλιοβασιλέματος, αλλά ένας τρόπος να δείξει τί σημαίνει να τα αναζητάς.

Κομβικό στοιχείο στη σύνθεση είναι η μεταμοντέρνα στρατηγική της ψευδαίσθησης και η διασταύρωση του ζωγραφικού και με το πραγματικό, την οποία ο Δρούγκας χειρίζεται με ευφυή επινοητικότητα: από τα πολυσχηματικά τελάρα μέχρι την αξιοποίηση του πλαισίου ως ενεργού στοιχείου της εικόνας (ψευδαίσθηση της κορνίζας), κι από την ενσωμάτωση αντικειμένων (φτερά παγωνιού, ξύλο ομπρέλας, κιάλια και άλλα) μέχρι λεπτομέρειες που λειτουργούν ως κλειδιά για την ερμηνεία.

Ένα τέτοιο κλειδί ερμηνείας είναι τα κιάλια. Δεν είναι διακοσμητική λεπτομέρεια, αλλά μια μικρή υπόδειξη για το πώς πρέπει να διαβαστεί ο πίνακας από τον θεατή: ψάχνοντας, όχι απλώς κοιτάζοντας. Εκεί όπου η γραφή λέει «κάπου εδώ υπάρχει», τα κιάλια υπαινίσσονται ότι το «εδώ» δεν είναι αυτονόητο, το βρίσκεις με το βλέμμα. Και επειδή μοιάζουν σαν πραγματικό αντικείμενο πάνω στο πλαίσιο, δυναμώνουν το παιχνίδι ανάμεσα στο ζωγραφικό και το πραγματικό. Έτσι, δεν μεγεθύνουν τη θάλασσα ή το ηλιοβασίλεμα. Μεγεθύνουν την ίδια την αναζήτηση του ορίζοντα.

Έτσι, το Εννοιολογικό Τοπίο, μετατρέπεται από απλό παράθυρο στη φύση, σε ένα σκηνοθετημένο πλαίσιο σκέψης, όπου η αρμονία της φύσης μπαίνει σε διάλογο με την τάξη και την καλλιγραφική δομή του γραπτού λόγου. Αυτή η αίσθηση κλίμακας και συμμετρίας, δεν είναι μια επιστροφή στο ιστορικό παρελθόν, αλλά ένας τρόπος για να γεφυρωθεί ο χρόνος, ώστε να συνδεθεί η ιστορία με τη σύγχρονη συνείδηση και να παραχθούν νέα ερμηνευτικά πλαίσια.

Όπως στην Χαμένη Récamier, όπου η απουσία της μορφής και τα απομεινάρια των αντικειμένων γεννούν μια ποιητική αβεβαιότητα, έτσι και στο Εννοιολογικό Τοπίο η γραφή προτρέπει τον θεατή, μέσα στο άπειρο «κενό» της φύσης, να δει αυτό το «κενό» ως χώρο σκέψης.

Στη διεθνή τέχνη, όποιος αναζητήσει παραλληλισμούς με το εννοιολογικό τοπίο ως «χώρο σκέψης», όπου η γλώσσα δεν λειτουργεί ως λεζάντα αλλά ως μηχανισμός θέασης, θα σταθεί στο διάσημο Ceci n’est pas une pipe (1929) του René Magritte με τη φράση τίτλο να δημιουργεί μια φιλοσοφική ρωγμή ανάμεσα στο αντικείμενο και την αναπαράστασή του[xi]. Θα αναφερθεί στο One and Three Chairs (1965) του Joseph Kosuth, όπου καρέκλα, φωτογραφία και λεξικογραφικός ορισμός συγκροτούν το τρίπτυχο πράγμα / εικόνα / έννοια, απαιτώντας από τον θεατή να διαβάσει το έργο ως ένα σύστημα σημείων[xii]. Θα μπορούσε να σταθεί στον Lawrence Weiner (από το 1968 και μετά) που καθιέρωσε τη γλώσσα ως υλικό του έργου και μετέθεσε το βάρος από το αντικείμενο στην ιδέα[xiii]. Επίσης, στη σειρά έργων του Ed Ruscha της δεκαετίας του 1960, με μεμονωμένες λέξεις σαν λογότυπα και αινιγματικά μηνύματα[xiv]. Σ’ αυτή τη διεθνή παράδοση, ο Δρούγκας αξιοποιεί τις στρατηγικές γλώσσας και εικόνας επιστρατεύοντας τη ζωγραφική του δεξιοτεχνία, ώστε το τοπίο να μην περιγράφεται αλλά να ενεργοποιείται ως νοητικό πεδίο. Οι λέξεις, η εικόνα και η ζωγραφική ψευδαίσθηση συνθέτουν έναν ορίζοντα που θεάται και ταυτόχρονα ερμηνεύεται αινιγματικά.

Τελικά, το Εννοιολογικό Τοπίο του Αχιλλέα Δρούγκα είναι μια ηθική της θέασης, δηλαδή ένας τρόπος με τον οποίο το έργο εκπαιδεύει το βλέμμα να μην καταναλώνει εικόνες αλλά για να τις διαβάζει και να απολαμβάνει την αβεβαιότητα της ερμηνείας. Δεν απαιτεί από τον θεατή να αναγνωρίσει έναν τόπο, αλλά τον εαυτό του στην αναζήτηση: πού τελειώνει το βλέμμα, τί είναι ο ορίζοντας, τί ψάχνει ένα καράβι, πού κοιμάται ο ήλιος. Και μ’ αυτήν την έννοια, η ζωγραφική του Αχιλλέα Δρούγκα, με το χιούμορ, την ειρωνεία, την επιμονή στη λεπτομέρεια και την τεχνική δεξιοτεχνία, υπηρετεί μια ομορφιά που διαλογίζεται.

Γιάννης Κολοκοτρώνης

Καθηγητής Ιστορίας και Θεωρίας της Δυτικής Τέχνης – Δ.Π.Θ. / Τμήμα Αρχιτεκτόνων Μηχανικών

Yannis Kolokotronis: Commentary on Achilles Droungas’ Conceptual Landscape

Can words give birth to an image? Yes—when they do not merely describe the world, but activate the viewer’s memory and imagination. Can words replace a landscape? Yes, if the aim is to convey an experience rather than a description: experience awakens memory, desire, nostalgia, and expectation. Why does a painter, through poetic reflection, paint a landscape? Because landscape is a way of thinking, not just nature. Because the questions “Where does the gaze end?”, “What does the horizon mean?”, and “What is a ship looking for?” are enduring questions—questions that lead us to seek meaning, not merely destinations.

SOMEWHERE HERE THERE IS

A LANDSCAPE

A SEA

A SUNSET

A BOAT

SEARCHING FOR

WHERE THE SUN SLEEPS

Achilles Droungas’ Conceptual Landscape is not a place to be copied, but a place to be contemplated. The landscape ceases to be a naturalistic representation and becomes a semiotic field—a scene in which things are not only what they appear to be, but also what they signify. For devoted admirers of his painting, such a work of image semiotics comes as no surprise. Droungas has accustomed us to an art that is unconventional, conceptual, symbolic, and allegorical—strikingly original—an art that, by exhausting the possibilities of extreme realism, is not confined to photographic fidelity but transcends it, drawing the viewer into an act of interpretation.

Achilles Droungas stands among the historical figures of contemporary Greek art, with an international trajectory that reaches back to the early 1970s. This recognition rests not only on the critical reception of his work, but also on its institutional record, as works by Droungas appear in major public and university collections, confirming his position within a broader international context (Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Tate Gallery (London), Portland Museum of Art, Buffalo AKG Art Museum, The University of Virginia, Cornell University, Victoria and Albert Museum, National Museum of Wales, Bibliothèque nationale de France (Paris), British Government Art Collection, National Gallery, among others).

Within this logic of extreme realism, the landscape can be born from words—not because words replace the image, but because they activate experience and expectation before that experience becomes image. “Somewhere here there is a landscape” is an invitation to the viewer’s gaze. And “the boat searching for where the sun sleeps” becomes an allegory of the human condition: a search along the horizon for the meaning of life. Thus, the conceptual landscape is not a depiction of the sea or the sunset, but a way of showing what it means to seek them.

A key element in the composition is the postmodern strategy of illusion and the intersection of the painted and the real, which Droungas handles with ingenious inventiveness: from multi-shaped supports to the use of the frame as an active element of the image, and from the incorporation of objects (peacock feathers, the wooden shaft of an umbrella, and others) to details that function as keys to interpretation. In this way, Conceptual Landscape is transformed from a simple window onto nature into a staged framework of thought, where the harmony of nature enters into dialogue with the order and measure of the written word. This sense of scale and symmetry is not a return to the historical past, but a way of bridging time—connecting history with contemporary consciousness and generating new interpretive frameworks.

One such key to interpretation is the binoculars. They are not a decorative detail, but a small cue for how the painting is meant to be read: they invite the viewer to search, rather than simply look. Where the text says “somewhere here,” the binoculars suggest that “here” is not self-evident—you locate it with your gaze. And because they appear as a real object on the frame, they intensify the interplay between the painted and the real. They do not magnify the sea or the sunset; they magnify the very search for the horizon.

As in Lost Récamier, where the absence of the figure and the remnants of objects give rise to poetic uncertainty, so in Conceptual Landscape the writing urges the viewer, within the infinite “void” of nature, to see that void as a space for thought.

In international art, anyone seeking parallels to the conceptual landscape as a “space for thought”—where language functions not as a caption but as a mechanism of seeing—will encounter René Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe (1929), in which the title phrase opens a philosophical rift between the object and its representation. One might also recall Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965), where chair, photograph, and lexicographical definition form the triptych thing/image/concept, requiring the viewer to read the work as a system of signs. Likewise, Lawrence Weiner (from 1968 onward) established language as the material of the work, shifting emphasis from object to idea. Also, Ed Ruscha’s word-based works of the 1960s, where isolated words operate like logos—enigmatic visual messages. Within this international tradition, Droungas mobilizes strategies of language and image while drawing on pictorial mastery, so that the landscape is not described but activated as a mental field. Words, images, and pictorial illusion compose a horizon that is both seen and interpreted—enigmatically.

Ultimately, Achilles Droungas’ Conceptual Landscape proposes an ethic of seeing: it trains the eye not to consume images, but to read them—and to take pleasure in the uncertainty of interpretation. It does not ask the viewer to recognize a place, but to recognize themselves in the search: where the gaze ends, what the horizon is, what a ship is looking for, where the sun sleeps. In this sense, Achilles Droungas’ painting—through humor, irony, meticulous attention to detail, and technical virtuosity—serves a beauty that meditates.

Yannis Kolokotronis

Professor of History and Theory of Western Art – D.U.Th. / Department of Architectural Engineering